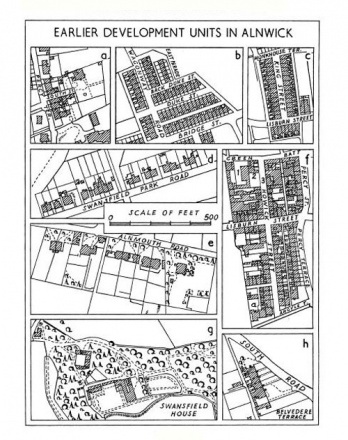

Figura que demonstra a expansão urbana na cidade de Alnwick, Inglaterra, em vários momentos de sua história: séculos XVIII/XIX, no histórico estudo de Conzen pai. CONZEN, M. R. G. Alnwick, Northumberland: A Study in Town-Plan Analysis

[fonte: Institute of British Geographers Publication n. 27. London: George Philip & Son, 1960, p. ]

Alessandro Filla Rosaneli e Dalit Shach-Pinsly: You introduce in your articles (1994; 1997) three schools of urban morphology: the Italian (with the founding contribution of Saverio Muratori), the English (represented by the initial work of M. R. G. Conzen) and the French (concentrated in the Versailles School). Besides great convergence of interests and the “type” as a common framework, you and others authors pointed out that the different languages and disciplines bring difficulties to build a convergent path. Do these problems remain today yet?

Anne Vernez Moudon: I guess the first thing to focus on is the similarities and the differences between the English, the Italian and the French Schools in chronological order. In a simple way, the English School was developed by Geographers. What do geographers do? They seek to be descriptive, they want to explain phenomena. The Italian School was started by architects, and what do architects do, they are interested in finding out about the kinds of buildings we should build and how we should design them. And the French School was started later, in the late 60’s. Its contributors were somewhat aware of the Italian School (they had found Muratori’s studies of Venice in a used book store in the late 60’s). The French School consisted of architects who were actually interested in Urbanism, and of Sociologists. In the 1960s, many architects were interested in the social aspects of the built environment. Both Panerai and Castex had taken courses with Lefèbvre and others French sociologists and geographers. Each School, because of its respective professional orientation had different purposes for the investigation of urban form. What I am trying to say is that, the geographers were interested in developing theories of urbanization, of how cities come about, but they were not necessarily interested directly in understanding or developing more prescriptive theories of how to plan cities. Whereas the Italians definitely were interested in developing theories of architectural design, building design, city design, and were therefore more proactive in their outlook than the British morphologists. The French were somewhat in-between (typical French) [rs]. They were critical of architectural design theories and they were interested in both the architectural and the urbanistic scales. But they were also interested in testing architectural theories. And they wanted to explore the origins of the theory the Moderns had proposed to make building blocks and to have streets at the level of the “superblock.” They asked when that movement and design emerge and how did it originate? They found that the theories of the Moderns had first been proposed in the nineteen century when parts of cities were already designed with superblocks.

Those are the three different interests that the three Schools had. They did have a common finding, that looking at the building on its parcel, or on its lot, was key to understanding urban form. Understanding urban form was understanding building types based on how the land was divided into discreet parcels that can be built on whether by individual builders or by land developers. The Schools all found that the lot or the parcel and the building(s) found on it, are key elements of urban form. I call the lot or the parcel the “pivot” of urban form, because it is the instrument with which one can understand building typologies, as well as how people live within buildings, and so on. From there, one can go “up” in scale, into how multiple lots or parcels are aggregated into street-blocks, and then how multiple street-blocks make up and form cities.

As an interesting aside, I called the three groups studying morphology ”schools” because I did not know what else to call them. When you do international work you have to find words that everyone understands and agrees on and words that will be “international enough” to be easily translated into different languages. So I proposed the word “schools” in 1997, when I did the retrospective on the three schools.. People in ISUF first liked it but on second thought, they wondered whether the three groups were actually “schools,” meaning that their members saw the research as coming from within an explicit set of theoretical questions and methodological frameworks. To tell you the truth I don’t entirely understand why they questioned the term, all I know is that ever since then, everyone referred to them as schools.

AFR / DSP: Talking about History and Geography, Peter Marcuse (1987) defends that the “city form is a residual”, that means, it is the result of the clashes of socio-economical and political interests. Thus, the urban design and planning, as an effort of professionals and technicians, have a secondary role in this process. In what measure do you believe that this limitation is an impeditive factor for better urban plans and projects?

AVM: I think that may explain why morphology “is” or “is not” considered as an important part of thinking about the city. For instance, Lynch was certainly more interested in the social, political, and psychological forces that shaped the city. He often said that he did not care about what the city was “physically” but instead cared about what “people thought or felt” about the city. Marcuse’s (and in essence, Lynch’s) has a “post structuralist”, “post constructivist” attitude, it could also be “Gestalt,” where the object (urban form) does not exist, except the eye to beholder. I have no problem with that stand as a philosophical one. However, this stand is instrumentally very limited, because it does not help us understand how cities are actually made. To understand how the city is made, going into people’s heads and figuring out how they conceive the city, how they want to live in it, etc., is not sufficient. We have to know “what” is being made as well, no matter how and why it’s made. The city is in part a collective object. A planner cannot easily go into the head of a collectivity and figure out exactly what they thought or wanted about their city. So, I think that considering or not considering the physical form of the city is a basic ideological and intellectual kind of issue that people like Marcuse and Lynch and so on, have unfortunately refused to face. While the city, the building, the street-block may indeed exist in the eye of the beholder, we as planners cannot take into the account all of the eyes of all the beholders, it is just a impossibility. In view of this impossibility, the planner can take an “artistic” approach and say, like Lynch, well, we will try to understand as much as possible how people conceive, understand, feel about the city, and then I will “go” from there and giving it my best and try working in groups to get to the collective shape of the city.

Myself, I take a “scientific approach” to understanding the objective and the subjective aspects of the city. When you look at what planners, urban designers, developers, builders, etc., really do, they built a “physical plant,” which is to say they create the objective reality of the city--that’s the only thing they can actually control. They cannot control what people think and eventually do about this physical reality. The political process is important; it determines why this developer or why this planner is selected rather than another. There is politics involved, and there is power involved. Politics are important to understand. Yet, when a decision is made, when a developer and/or a planner are selected to develop a part of a city, whether the person or a group is from the left or from the right, they only have control on the city as a physical object. I’m sorry if I disappoint you! But this is why I think that urban morphology and the objective aspects of the city are essential to consider. This object quality of the city may not (even never) really exist as such in people’s minds, but it is an essential baseline component of the planning process: it is the only thing we can measure objectively, meaning that the physical object is what we can agree on, and what we necessarily share. This physical dimension of the city is a common baseline from which we can then assess subjective aspects such as preference, meaning, usefulness, etc. In that sense, we have to use an urban morphological approach, which is an object oriented approach, not because it is the “truth”, or the “best,” but because it is the only common base from which you can measure everything else. So I often say to students: “you do not make “place,” you make “space.” Some people get horrified, because they so much want to make “place.” The fact is that planners, designers, and developers cannot directly shape people’s thoughts or even behaviors, hence they cannot “make place.”

But back to Marcuse, I agree with him that planning is limited, and when an area is planned, chance and hazard come into the picture, and the space made may not match the intended users’ expectations or needs. On producing urban form (space more than place), planners and designers should generally look for the “greater good” in the long term, they should have grounded historical knowledge, and they should try to introduce change gradually. They should not look for tomorrow’s market, but for the value of the built environment over several generations.

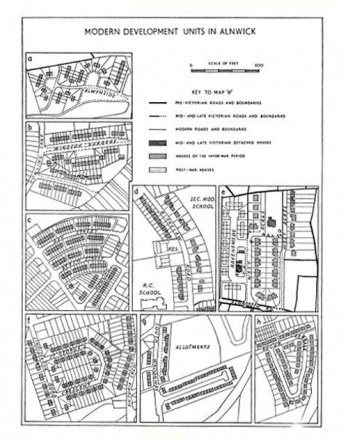

Figura que demonstra a expansão urbana na cidade de Alnwick, Inglaterra, em vários momentos de sua história: século XX, no histórico estudo de Conzen pai. CONZEN, M. R. G. Alnwick, Northumberland: A Study in Town-Plan Analysis

[fonte: Institute of British Geographers Publication n. 27. London: George Philip & Son, 1960, p. ]